One of Simon and Garfunkel’s early hit songs, “The Dangling Conversation,” had in it these memorable lines:

Yes, we speak of things that matter

With

words that must be said

“Can

analysis be worthwhile?”

“Is

the theater really dead?”

In

light of a couple of recent articles I’ve come across, those lines makes me

think of how critics and writers always predict the demise the novel. Is the

novel really dead? A lot of modern critics would have us think the novel is

dead—or, if not dead, on its last legs and soon to be deceased. I would like to

explore this topic a little bit in a couple of blogs. It would seem that merely

saying, “No the novel is not dead” would be sufficient if you don’t hold to

that particular view (which I don’t). But the issue is complex and, based on

assumptions that are complicated and intricate.

The

idea that the novel is dying, that writers have reached the end of a genre,

which may be proclaimed “the death of the novel,” is nothing new. Its demise

has been predicted many times. In 1967, novelist and literary critic John

Barth wrote a much-anthologized essay called “The Literature of Exhaustion,” published

in The Atlantic later that year and

widely reprinted.

Barth

thought that novelists had exhausted all possible forms and plots and could

only imitate other

novels and do nothing really original. Of course, his

sentiments were nothing new. Novelist Jose Ortegay Gasset wrote The Decline of the Novel in 1925; critic

Walter Benjamin in 1930 penned Crisis of

the Novel—the list could go on. All were certain the novel was on its way

out and would be replaced with other literary forms. All were certain no one

could come up with any new ideas that would keep the novel . . . well, novel.

|

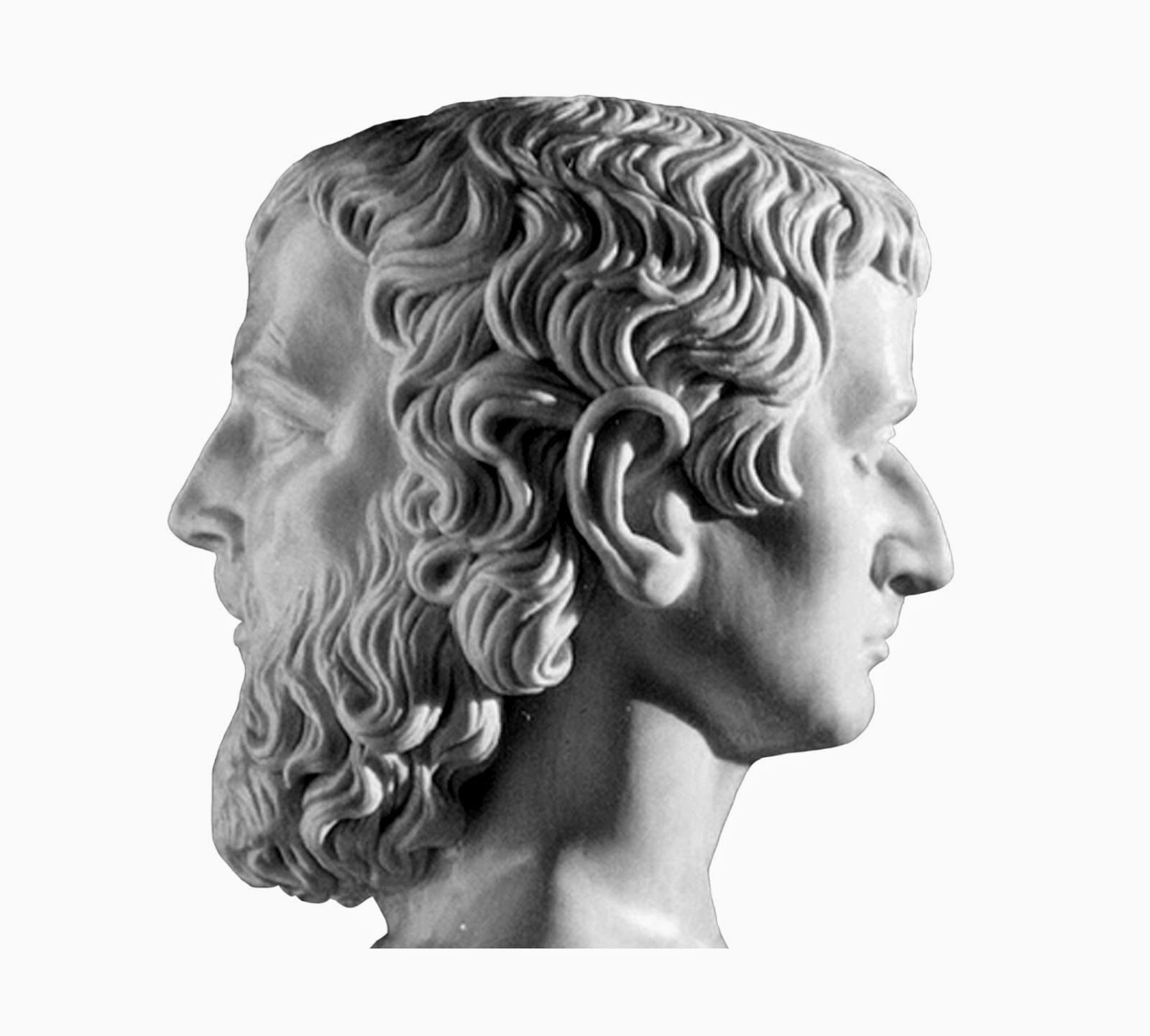

| John Barth |

Here’s a point that may seem esoteric but I think bears mentioning. The novel is a new art form. It’s only been around for about 300 years, as opposed to theater and poetry, which have been around for thousands of years. In fact, novel means “something new or unique,” which is what the form of a long prose narrative centered on conflicts characters faced and how they change or don’t change in the course of the conflict constituted in the later 1600s, when Samuel Richardson penned what it generally considered the first novel, Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded. It was something innovative and brand new. Perhaps since the novel is new, in terms of other literary forms, many think it’s just a fad—a 300 year-old fad, but what’s 300 years in the history of literature?

It

can also be said that these claims are obviously not true.

Contemporary novels like Gone Girl, The Lovely Bones, Wolf Hall, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, A Visit from the Goon Squad, Blood Meridian, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, and a host of others have sold well, been made into films, and (most importantly) have demonstrated innovative technique, forms of narration, strategies for writing, and modes of language use. The examples I gave here are from the grouping called “literary fiction,” but add in popular fiction—Steven King’s novels, The Hunger Games series by Suzanne Collins, John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars (again, the list could go on and on); add what is called “popular fiction”—and the novel seems not near death but very spry and quite capable of running a marathon.

Contemporary novels like Gone Girl, The Lovely Bones, Wolf Hall, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, A Visit from the Goon Squad, Blood Meridian, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, and a host of others have sold well, been made into films, and (most importantly) have demonstrated innovative technique, forms of narration, strategies for writing, and modes of language use. The examples I gave here are from the grouping called “literary fiction,” but add in popular fiction—Steven King’s novels, The Hunger Games series by Suzanne Collins, John Green’s The Fault in Our Stars (again, the list could go on and on); add what is called “popular fiction”—and the novel seems not near death but very spry and quite capable of running a marathon.

So why all the predictions of the novel’s demise?

As I said, the reasons are complex. They are related to how certain authors wanted to define the genre of novel; to a bit of egotism on the part of authors who thought their creations were the be-all and end-all of literature; on chauvinism and Western-centric ideology; on misunderstandings of human creative capacity; on old-fashioned intellectual arrogance and undemocratic elitism.

The resilience of the novel’s form is apparent in the works listed above. The various novels categorized as literary fiction break barriers and take novel writing into new, fresh territory. Many were written by women (as are a good chunk of the novels that are highly popular today). Some come from writers of non-Western cultures.

And while I think the predictions are wrong, looking at them is instructive. The next couple of blogs will tackle the subject of novel writing and will speculate on the why. And we’ll go from the why to the what. How will the novel continue to change and grow as the years progress?

The resilience of the novel’s form is apparent in the works listed above. The various novels categorized as literary fiction break barriers and take novel writing into new, fresh territory. Many were written by women (as are a good chunk of the novels that are highly popular today). Some come from writers of non-Western cultures.

And while I think the predictions are wrong, looking at them is instructive. The next couple of blogs will tackle the subject of novel writing and will speculate on the why. And we’ll go from the why to the what. How will the novel continue to change and grow as the years progress?

Check out some of my novels at my Writer's Page. If reading is part of your New Year's resolve, or if you simply want to start the year out with innovative books to read, I recommend The Gallery, Strange Brew, The Prophetess, and The Sorceress of the Northern Seas.

Check out the Horror Maiden's review of my book, Strange Brew.

Read my interview with Micro-Shock.

Have a happy New Year.